An HR executive recently told me with great frustration how her company was struggling to improve gender parity in leadership. Despite efforts to promote more women into high-visibility leadership roles, the company’s progress had stagnated. Gender bias in leadership had become a real issue.

She recounted a time when, a few years ago, a talent review identified three women directors as high performers with high potential for growth into a VP role. These women were promoted, and the decisions were met with nearly universal acclaim. These were proven, long-tenured women leaders with track records of success. Many in the company felt that the promotions were, quite frankly, overdue.

As of today, none of these women remain at the company. So what went wrong with these transitions?

In DDI’s Leadership Transitions Report 2021, we gathered data to provide evidence-based answers to why leadership transitions fail. This research also aims to identify the factors that disproportionately hurt the transitions of women.

Gender Bias in the Pipeline

Our research shows that women at every level receive less support in their transition to leadership. And they also report higher levels of stress in their transitions. On top of that, a larger percentage of men indicated being given clear expectations for success in their roles than women.

The bottom line? Women aren’t given the same development opportunities that men are given. And this hurts the ability of women to not only advance, but if they do make it to leadership, they aren’t set up to succeed.

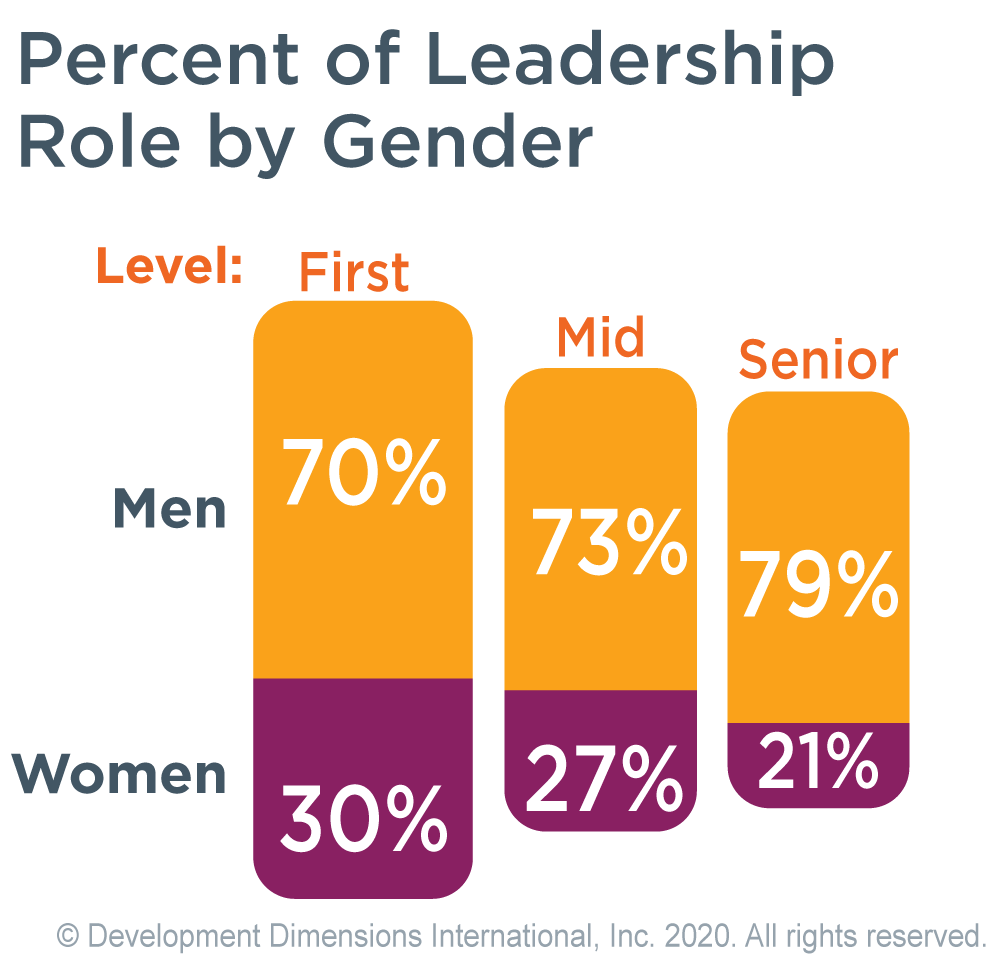

Another sobering statistic? We found in our Diversity & Inclusion Report that 45% of women executives feel they would need to switch companies to advance (compared to 32% of men). With a mere 21% of women making it to the senior executive level, the data suggest a much narrower path to the top for women.

In a highly competitive labor market, companies can’t afford to ignore these differences. In the war for talent, the winners are figuring out how to maximize the potential of their entire workforce. They address gender equity as a strategic talent priority, not just a diversity initiative. Especially as the business benefits of having gender and ethnic diversity are well known. As our research found, companies with above-average gender and racial/ethnic diversity are 8x more likely to be in the top 10% of organizations for financial performance.

One reason efforts to get more women into leadership roles fail is that they focus on the outcome—gender parity—instead of the root causes—systemic inequity. These inequities don’t disappear the day a woman is promoted into her next leadership job. They just become harder to spot.

Gender Bias in Leadership Starts Immediately

Our research uncovered a number of ways women aren’t set up for success as well as men from day one in a leadership position.

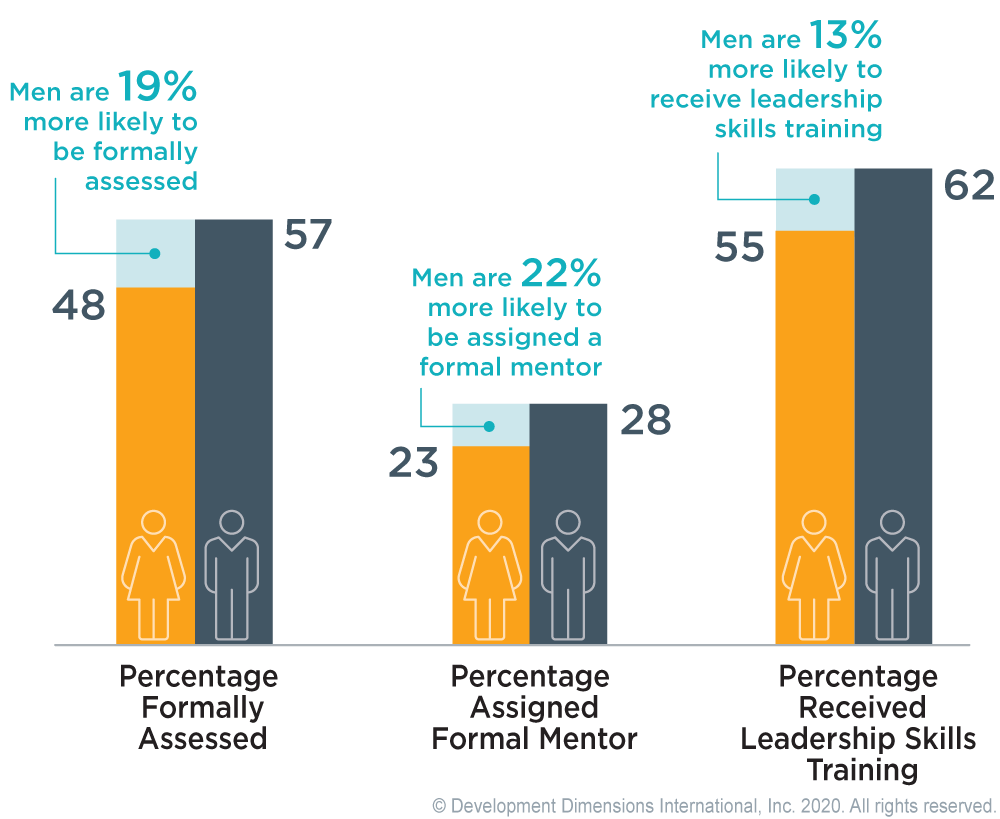

Men were 19% more likely to have been formally assessed as a part of their transition. Assessment enables smoother transitions. How? The leader, their immediate supervisor, and HR are given visibility into the development needed to succeed in the new role. This provides a level of support and insight that is crucial during what can be one of the most challenging and stressful moments in a leader’s career.

Men were also 22% more likely to be assigned a formal mentor than women leaders. Mentorship opportunities are highly susceptible to affinity bias (the unconscious tendency to prefer interacting with people like us). Additionally, in the #metoo era, 60% of male managers say they’re uncomfortable participating in workplace activities with women. This includes mentoring and other socializing that provides access to information, opportunities, and relationships that enable career success.

This puts women, who are already underrepresented in leadership, at a disadvantage in finding a formal mentor. Informal mentorship opportunities can be even more prone to this bias. Because they evolve more organically, the chances of buddying up with someone who is like us is even higher.

Women were also at a disadvantage in their access to formal leadership development experiences. Men were 13% more likely to have received leadership skills training than women.

The Glass Cliff

Compounding these inequities is what’s known as the “glass cliff” phenomenon. This is where women are promoted into challenging leadership roles when times are tough, or the organization is in need of a transformation. If the glass ceiling is what barriers women face as they ascend to positions of power, the glass cliff occurs when women are put into risky leadership positions where the chances of failure are high.

This was the case in the company I mentioned earlier. They promoted one of the women to lead a division that had been struggling to perform for years. As time went on, she grew increasingly concerned that she was losing senior leadership’s support.

Without a mentor to turn to or clear guidance for how to develop into her VP role, she left the company for a fresh start. And even worse? She took a job with one of their competitors. The HR executive reflected, “By the time we finally got a plan in place to help her as a new executive, it was already too late.”

Recognizing Gender Bias in Leadership

It can be easy to spot the effects of gender bias in leadership by looking at an org chart. Getting data to explain the “why” takes considerably more effort.

To recognize the complexities that hinder women’s advancement, we must be willing to do a thorough analysis of talent metrics and systems. What hidden obstacles to successful transitions exist? Where are we most vulnerable to gender bias in leadership? Here are a few questions to ask:

1. Are you looking at the whole pipeline?

Gender equity has traditionally been spoken about as who makes it to the C-suite. However, the gender leadership gap starts with the disproportionate number of women who never get a chance at leadership. What support are you providing to aspiring leaders who are reaching for the first rung of leadership?

2. How deep is your pool?

Ensuring you have an adequate pool of candidates is critical. For half of CEO jobs, a woman was never considered in the pool. And when there was only one woman, she was never selected.

3. What selection and promotion practices are most vulnerable to gender bias in leadership?

Unconscious bias can’t fully be driven out of your processes, but its effects can be managed. Objective assessments drive fairness and equity in hiring decisions and smooth leader transitions.

4. What measures show equitable transition support?

Many companies set goals for gender representation at different leader levels. However, few do as well at measuring indications of smooth transitions and adequate development support. Analyze your talent practices for equitable gender representation in formal development programs and look at who is getting stretch assignments. Consider developing an acceleration dashboard with an eye toward gender diversity and make it visible to senior leadership.

5. Is it time to rethink your approach to mentorship?

Set clear parameters for what a mentor relationship should be and empower women to find the right one. Mentor matching often focuses on “style fit” or compatible personalities. And this comes at the expense of picking the mentor with the skillset most aligned with the challenges of the new role.

Equip Women with Skills

When DDI synthesized the results of 15,000 executive assessments in our database, we looked at whether there were differences in skill levels of candidates by gender. We found no statistically significant difference between men and women in their readiness to tackle the key challenges of the roles they were applying for.

If there isn’t a fundamental difference in skills, what kind of differential development support should companies provide to women leaders?

Women—like other populations underrepresented in leadership—must overcome the systemic challenges that make their transition into a leadership role more challenging. As a talent professional recently confided to me, “we can’t act like everyone is pushing at the same open door.”

There are unique obstacles that face women leaders at all levels. DDI’s Ignite Your Impact: Women in LeadershipSM series helps current and emerging women leaders develop skills to build confidence, strengthen their networks, and build their leadership brand.

Companies like Sparrow Health System have used this content in high-potential programs aimed at closing the gender leadership gap. The results have been powerful. Women who participated in Sparrow’s women in leadership program far outpaced their counterparts in the rest of the organization in engagement and retention.

Even more importantly, 24% of the women who participated achieved a promotion during or after completion of the program. This included two women promoted into key director roles. And because of the high level of transition support they received, they’ve been set up for a smoother transition with a greater likelihood of long-term success.

In Conclusion:

Combatting Gender Bias from Day One

To achieve gender parity in leadership, companies must provide equal access to the kinds of development and support that can make or break a leadership transition. Lacking transition support can have a compounding effect on women as they progress in their leadership career. This makes each transition increasingly risky.

By providing equal access to high-quality leadership behavior and skills training, developmental assessments, and opportunities for mentorship and network building, companies can build a stronger, gender-diverse leadership pipeline.

Get more research by downloading the Global Leadership Forecast 2021.

Mark Smedley is a leadership advisor for DDI. He is passionate about helping organizations use research-based methods to integrate their diversity, equity, and inclusion priorities into their leadership strategies.

Topics covered in this blog